Pabean Temple on Bali’s North Coast Faces the Sea, Preserves Ancient Port Customs

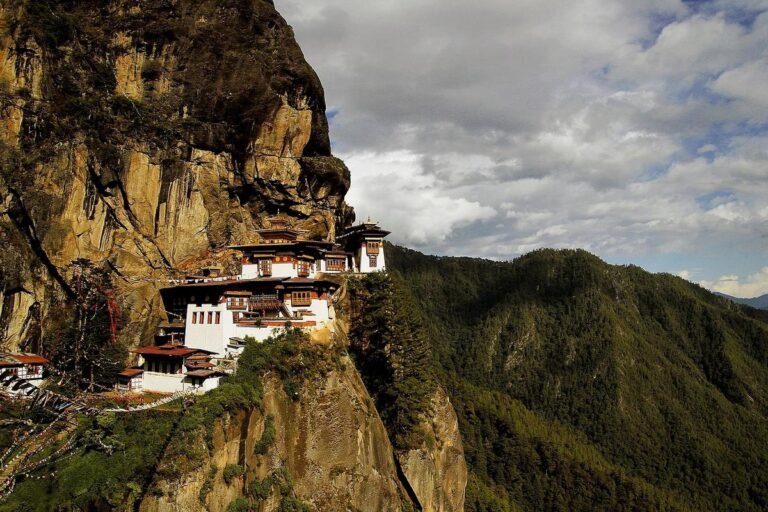

Buleleng Regency’s Pabean Temple perches on a rocky outcrop above Bali’s northern shore, where visitors can gaze across the Bali Sea. Its position draws attention for unobstructed ocean views that accentuate calmness. A low rise of native shrubs surrounds the site, guiding the eye toward carving details on gates and temples. The location is celebrated for its architectural harmony, meaningful ornamentation and integration of local belief systems. At sunrise, glowing skies reflect off carved temple walls, casting long shadows across mossy stones.

The temple’s name traces back to “bea,” a term for port taxes on shipping cargo. A prefix “pa” and suffix “an” combine to form “Pabean,” marking a common stopping point for trading vessels. Historic records link the temple to maritime customs, and its grounds follow traditional Balinese principles with three distinct sections. Legends mention that ancient mariners offered prayers here before departing.

Balinese temple design assigns Pabean Temple an outer courtyard, a middle compound and an inner sanctuary. The outer ring, jaba sisi, includes a pathway that leads past the Gelung Kori gateway into the front courtyard. The middle ring, jaba tengah, holds two Wantilan halls for community gatherings, a Bale Peninjauan pavilion and a tall Bale Kulkul tower. Orientation toward kaja, the mountain, and kelod, the sea, creates a straight axis linking each area to the inner shrine. At that sacred center, the Padmasana shrine sits in the innermost zone, jeroan, and honors Hyang Maha Tunggal with ritual offerings and incense.

Within the inner sanctuary, a line of shrines surrounds the main Padmasana altar, decorated with golden reliefs of Acintya and carvings of aksara ongkara. Nearby stands the Palinggih Pengaruman Agung, an eight-sided pavilion symbolizing the cardinal points. Side shrines, including Lingga Ida Batara Baruna and Palinggih Dewi Kwan Im, feature Chinese-style dragons entwined around pillars and ancient coin motifs carved above doorways. Each shrine blends Balinese Hindu symbolism with Chinese elements, making the complex a study in cultural fusion and sacred architecture.

Architect Ida Bagus Tugur chose black paras stone as the primary building material, carving every platform, gate and terrace from this volcanic rock. Work to restore the site began in 1995, prompting a temporary transfer of the Ida Batara Pabean family deity to a nearby location south of the temple. A malaspas alit purification ceremony marked a key ritual in 1999. On November 19, 2002, the ngenteg linggih consecration ritual coincided with the island’s fifth full moon and the Penampahan Galungan festival. Coastal excavations have brought to light Chinese porcelain fragments and human skeletons carbon-dated to the Yim Dynasty, roughly 2500 BCE, tying the site to early trading routes.

Local lore records the arrival of Dang Hyang Dwijendra from the central coast, where he found Ida Batara Pulaki already established at nearby Pulaki Temple. Jero Mangku Teken relates one story in which Ida Batara Pulaki took on a human shape missing both arms and legs to test the visitor’s spiritual power. Trade vessels from China, the Bugis archipelago and Malay kingdoms shaped everyday life on this shore, weaving diverse customs into the temple’s ceremonies and decorative carvings, and underscoring its role as a meeting point for regional cultures. Historians note the carvings on its walls blend motifs from local and foreign iconography, a visual record of centuries-old exchanges.

The main entrance, known as Gelung Kori, features a pair of heavy stone gates topped with semicircular ornaments inspired by seahorse shapes and monkey figures carved along the arch. A circular path winds around a low hill pointing directly toward Pulaki Temple. This route resembles a turtle flanked by two dragons, Anthaboga and Basuki, with the dragons’ heads turned toward the sea and their tails aimed at nearby mountain slopes. This design reflects a balance of land and water, with each curve and motif carrying layers of philosophical meaning. Pilgrims trace this path in clockwise walks and leave offerings at key points.

Down the slope, two smaller sanctuaries named Linggih Dewa Ayu and Linggih Patih Agung stand built from smoothed coastal stones. Architect Ida Bagus Tugur fashioned these quiet spots as places for rest between ceremonies. Each pavilion opens to views of palm groves and the ocean horizon. A stone-floored walkway links the sanctuaries to the main complex, inviting visitors to reflect beneath open sky and sea breeze before returning to the central shrine.

Temple guides remind visitors not to feed the troops of macaques that roam freely among the gates and shrines. They encourage respectful observation as the monkeys explore rock crevices and gather near offerings laid by devotees. This lively presence brings a natural element to the temple grounds.

Pabean Temple’s architects and priests crafted an inclusive shrine layout that blends Hindu and Chinese spiritual traditions under Indonesia’s motto “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” (Unity in Diversity). At each corner of the compound, worshipers find sites dedicated to local deities, ancestral spirits known as Ida Batara, and foreign gods venerated by trading communities. The Palinggih Dewi Kwan Im pavilion honors the Goddess of Mercy; the Lingga Ida Batara Baruna shrine acknowledges the sea god. Daily offerings of flowers, incense and small fruits continue a practice that reaches back through generations, confirming the temple’s role as a crossroads of faith along Bali’s northern coast.